700 words (3 minutes reading time) by Tim Whistler

‘The IT Wager’ by Tim Whistler (with the assistance of ChatGPT)

Carole Parkinson has put together a compelling and well researched post on how Councils can avoid gambling on IT investments – or at least how the risks in the bet can be understood.

I asked some experienced IT managers what they thought and they said the post was useful but didn’t go far enough.

I asked them why.

Why the IT bet feels safer than a service bet

The first point made was that the post should have explored why CEOs prefer to gamble on an IT bet than a service review and improvement bet. It was suggested that perhaps they didn’t understand how to make the service review and improvement bet. Or it was simply easier to bet on an IT product from a big vendor. It is a way for the CEO to outsource risk. They pass on the responsibility for organisational service improvement to a Big 4 consultancy and the software vendor.

One suggested that CEOs don’t have a choice because they are caught up in the race to digitise simply because their councils and communities expect them to do it. It is the new service standard. Non one wants to be left behind. Whilst this may be true, I have never seen a business case with a justification of ‘they are doing it, so we should too!’.

Why business cases mislead

The second point was that excessive optimism is just one of the judgement errors CEO’s and councillors make. This could have been explained more. They saw it as accompanied by overestimation of benefits and underestimation of risks. Of course, they are related and Parkinson could have discussed how this occurs in the benefit:cost analysis of the business case. I suppose, in fairness to Carole, she did say to treat the business case as a ‘claim to test, not a plan to implement’. She encouraged Councillors to question the way benefits and risks are quantified.

What vendors actually guarantee

The last point they made was on vendor assurances or guarantees that their software will deliver the expected benefits. I was told attempts to set this up had all failed. A quick search using ChatGPT revealed that software vendors will provide some assurances. For example, the uptime/availability of their software for use by the purchaser. Typically there are numerous exclusions, remedies or damages are limited, and there is seldom compensation for losses. But they do provide it.

Vendors will also warranty that their software will conform with their specification and documentation, and they will rectify any defects. They don’t warranty that the software will achieve what the purchasers specification requires or transform their services. Whilst vendors often claim that their software will improve productivity/efficiency/service experience, their contracts don’t guarantee it.

To get a guarantee of business improvement, a purchaser would have to explicitly turn their expected operational outcomes into contractual obligations with measurement linked to payment – and then get the vendor to agree. This is unlikely to happen with the big software vendors because they would be taking on much more risk. It would also be reflected in their price if they did agree. Expect to pay a lot more.

In the end…

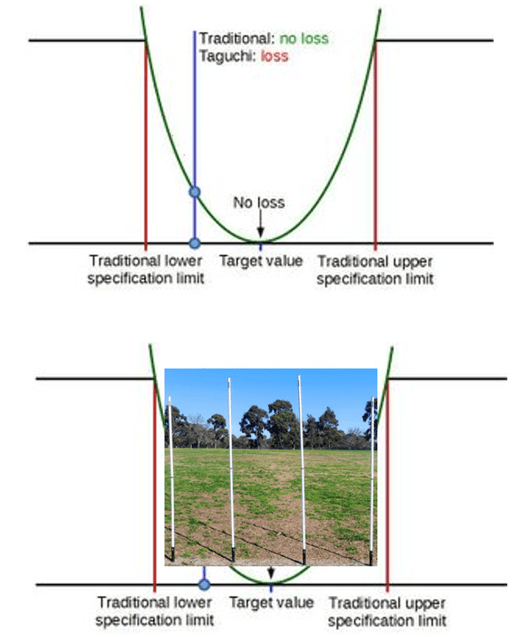

In the end, the uncomfortable truth is simple: vendors will stand behind availability and conformance to documentation, not the operational outcomes your business case is counting on. It is illustrative to think of an outcome guarantee as if it was a bet.

If the benefits in the business case are real and predictable, the vendor should be prepared to place a bet by putting meaningful fees at risk. This would help the council to monetise the risk it would otherwise take because the price of getting the vendor to accept the risk would equal the cost of the risk.

If the vendor won’t place the bet, why should the council?