1200 words (10 minutes reading time) by Lancing Farrell

This second post continues my management journey back into local government. This time into the wasted years – time spent trying different management ideas without success.

Some 10 years later I re-entered local government in a management role. Now we had new management ideas, some even described to me as ‘fads’. In the time I had been out of the sector, the idea of management had gained more currency. I came across Evidenced-Based Decision Making, although as some colleagues pointed out, in practice it was more commonly ‘decision-based evidence making’.

Evidence-based management is an emerging movement to explicitly use the current, best evidence in management and decision-making. It is part of the larger movement towards evidence-based practices.

I found a very interesting sounding book at this time called The Knowing Doing Gap by Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert Sutton. The title seemed to say it all – how can organisations put their knowledge into action and be more successful? I would like to say this book changed my life, but unfortunately it didn’t. Before I could read it thoroughly, I lent it to a colleague who never returned it. That closed a knowing doing gap for me – don’t lend other people your new books!

I found that Employee Surveys had now become common place. Councils were now being managed by CEOs who ‘took the temperature’ of organisational culture and then developed plans to improve it. I was never too clear on the connection between culture scores and value for customers or the community.

Employee surveys are tools used by organizational leadership to gain feedback on and measure employee engagement, employee morale, and performance.

These surveys tended to show very little change from one survey to the next, even over a decade. It suggested to me that it wasn’t helping (or relevant) but we still did it. Once I looked at a book produced by one of the big culture survey firms and I noticed that our organisational culture resembled the culture of every industry they surveyed in Australia (except industries with lots of international firms). The differences between industries were at the margins. It seems Australian culture dominates in all Australian workplaces.

After a while, I started working at a council that was implementing the Australian Business Excellence Framework (ABEF). As someone who by now was quite interested in what local government thought was good, or even better, excellent management, this seemed like a useful idea. There were lots of other councils using it (some were Gold medallists) and it was an idea developed in the private sector, which had appeal to me after returning from working in my own business. So, I joined the strategy and planning group. The CEO had decided ABEF implementation would start with that category.

The EBEF framework and categories.

I found this interesting because I would have started with Leadership, simply because of its potential to effect change and improvement. Since then I have learned that you can start with any of the seven categories. My question today would be why not start with the customer? In this time I was able to travel and meet with officers at award winning Australian councils and spent hours studying organisational strategy.

Examining how councuil strategy and planning works only highlighted for me the dysfunction in council strategy development, with various types of plans in a hierarchy (you guessed it, a triangle) with different plans or strategies created at different times and in different ways. None of it was connected in the way the triangle suggested, and, in a surprise to everyone, the group worked out that one of the key plans linking political and organisational actions, didn’t actually exist except in the triangle picture used by the CEO to explain how it worked.

The Australian Business Excellence Framework (ABEF) is an integrated leadership and management system that describes the elements essential to organisations sustaining high levels of performance. It can be used to assess and improve any aspect of an organisation, including leadership, strategy and planning, people, information and knowledge, safety, service delivery, product quality and bottom-line results.

I then discovered Lean and found that it was the new version of TQM or BPR. It seemed to embody similar thinking ideas. I never bought a book on Lean but I started working at a council with a Lean practitioner. He (and many others) spent a lot of time analysing services that weren’t working. Hours were spent collecting data and mapping processes. Days trying to understand what the data was saying and where change might make it better. In the end, while chnages were made, the problems remained unsolved.

My involvement with cross-organisational business processes led me to Karen Martin’s book The Outstanding Organisation, and then her next book Value Stream Mapping. It seemed simple, we just had to learn to understand services as a value stream and then articulate and deliver the value proposition!

A value stream depicts the stakeholders initiating and involved in the value stream, the stages that create specific value items, and the value proposition derived from the value stream. The value stream is depicted as an end-to-end collection of value-adding activities that create an overall result for a customer, stakeholder, or end-user.

Around this time there seemed to be a ‘wave’ of people-based change programs. Leading Teams and The Colloquium are examples. CEOs were clearly searching for ways to act on culture and improve survey results. No doubt these programs were useful, but building people skills wasn’t making the difference CEOs expected. I participated in one of these programs and learned a lot. It was extremely useful to me as a person responsible for managing other people. However, it didn’t help me or my organisation to produce better services.

As an aside to my management journey, in 1995 I had discovered Public Value (yes, I bought Mark Moore’s book Creating Public Value) and the idea appealed to me enormously. Of course, council services are intended to produce the value agreed by people in the community, after all, they are the ones who are paying. In 2013 I bought Mark Moore’s second book (Recognising Public Value) where he illustrates the creation of public value using case studies and describes a way of measuring it (the Public Value Scorecard (PVS)). There is no arguing with the logic of Moore’s strategic triangle, but I couldn’t work out how to use it. Even the PVS was a lagging measure – you would only know if you had succeeded or failed, when you had either succeeded or failed.

I will mention one last management fad that swept local government here recently – User-Centred Design (UCD – there always seems to be an acronym). The council I was working at made a commitment to ‘customer first’ and commenced the analysis and re-design of services using the UCD methodology. We developed personas, customer apps, online forms. It really should have been called ‘digital first’. The problem that emerged was lack of integration between these new and easier ways for customers to deal with us and the actual service delivery systems. It had become easier for customers to make their needs known to us, and to place a demand on one of our service systems, but we were just as slow to respond, and just as likely to fail to satisfy their need.

The upshot of all my thinking and doing was a level of dissatisfaction with the way things are and a determination to find a way to deliver better services. I felt a compulsion to do this as rate capping was reducing our revenues and making it harder to make ends meet. A better way was needed.

Another pattern had emerged – I was now interested both in services as a cross-organisational process, and how you help an organisation to change and improve services.

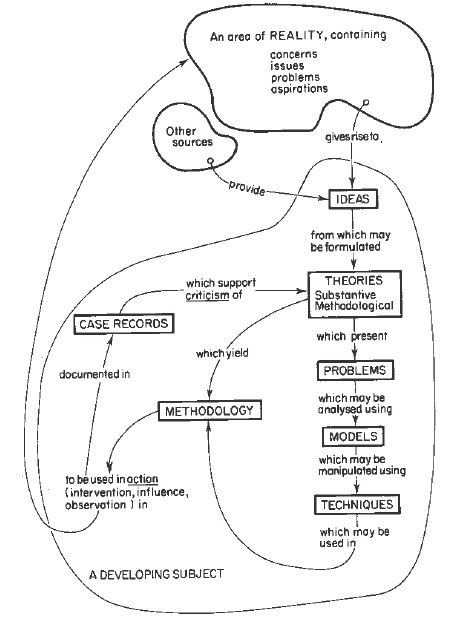

It was at this time that I recalled some earlier reading I had done on systems thinking and the application of systems thinking in organisations. It started with Alistair Mant and his excellent book, Intelligent Leadership, that I had purchased in the late 90s. I also bought and read David Wastell’s book Managers as Designers in the Public Sector, and through that book came across John Seddon’s book, also from the Triarchy Press stable, on Systems Thinking in the Public Sector. The idea that systems thinking could provide a solution to service improvement became clear in my mind.

I also became convinced that Command and Control thinking (a term used by John Seddon) was a barrier to service improvement. Councils are highly siloed organisations. We like functional specialisation. Each discipline focuses on their work and excelling at what they do. Hierarchy is critical for decision making and it is often the only way that the silos become linked. Senior management have the ‘umbrella’ jobs that integrate work across silos, or at least that is where it can and must happen in a Command and Control hierarchy.

I started looking for more information about systems thinking. At some stage I came across David Stroh’s book Systems Thinking for Social Change. By then I was hooked. There had to be a way of applying systems thinking to improve local government performance in delivering services that provides public value. The challenge was to find a method to do it. The ideas were interesting and well-articulated, but how do you use them to do the work differently?

By now I had begun blogging to communicate with others experiencing the same frustrations as me. It helped me to learn.