3100 words (15 minutes reading time) by Colin Weatherby

Podcast option:

Credit: ChatGPT

Summary

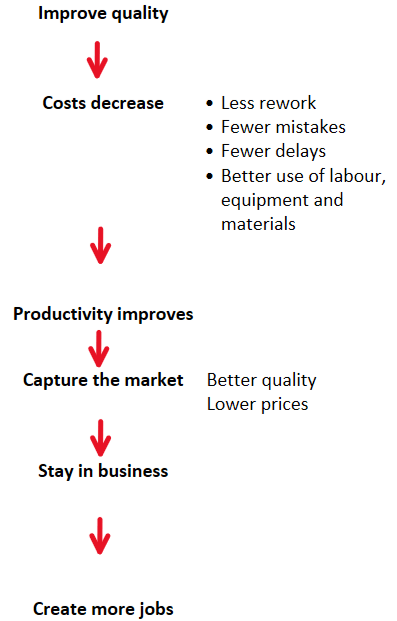

- Councils under rate caps are being pushed into a capability trap: cutting investment in how work is done, while demanding the same (or more) output.

- Doing more with less works for a while, then it quietly destroys the ability to deliver safe, reliable services.

- Escaping the trap means shifting from “work harder” to “work smarter” – investing in process capability, not just pushing people to do more.

- This piece explains the trap in plain language and offers advice to avoid it.

Introduction

After ten years of “doing more with less”, many council roads managers describe their world like this:

“Today, I barely recognise our roads program. Every budget cycle we cop another efficiency dividend, another round of ‘temporary’ cuts to inspections, reseals, heavy patches and drainage repairs. On paper the program still looks coherent thanks to some clever rephasing and optimistic assumptions, but out on the network the cracks are literal.

We’ve gone from renewing assets at the right time to stretching them well past their use-by date. Crews that used to do planned maintenance now spend most of their time chasing potholes and complaints. We’ve sweated the plant so hard that breakdowns are normal, and cut training and supervision to the point where we’re relying on a few old hands to hold everything together.

What hurts most is knowing this was avoidable. Every ‘saving’ we booked was borrowed against the future condition of the network. We’ve lost capability in quiet ways – trainees we didn’t take on, engineers who left and weren’t replaced, inspectors who no longer have time to inspect, relationships with contractors hollowed out by always taking the lowest price.

The community still expects the same level of service, but we’re no longer set up to deliver it. We’ve traded investment in capability for short-term budget wins, and now the bill is arriving as risk, backlog and a network that’s deteriorating faster than we can look after it.”

This isn’t a story about lazy workers or bad managers. It’s what it looks like when a council slides into what Repenning and Sterman call the capability trap – without realising it.

Continue reading