2200 words (20 minutes reading time) by Carole Parkinson

Podcast option:

Credit: ChatGPT

In a nutshell…

This post explores the risks and pitfalls associated with large-scale IT investments in local government. It argues that councils often rely on technology and automation to fix financial deficits or service inefficiencies without first optimising their underlying processes. Drawing on expert theories, the post suggests that these ambitious projects frequently over-promise and under-deliver by ignoring the complexities of human-technical systems. To avoid failure, Parkinson recommends that leaders adopt a skeptical mindset, demand evidence-based service studies, and implement incremental project stages. Ultimately, Parkinson emphasizes that improving service design from a resident’s perspective is more effective than simply digitising outdated methods.

Introduction

“I voted for the IT project because the business case promised the budget would balance by year four. But no one told us what we’d do if the savings didn’t arrive. In the end, we automated our inefficient services instead of fixing them. It has now cost us more money than we have saved!

We should have demanded a service study to improve services first, limited the project scope, put a ‘kill-switch’ in place, and made sure the CEO had an effective early warning system in place for failure.”

Councillor

The lesson?

Big IT doesn’t fix services; it just automates them. You can make governance improvements to reduce the odds of an expensive disappointment.

Why councils are betting on IT

I have been reading the plans Victorian councils are releasing for the next 10 years. These plans are all a bit different. In essence they cover how a council will serve its community, define the services and projects the council will deliver, and show how the councils strategic direction will be funded.

IT investment is positioned as an enabler of efficient service delivery, better decisions, streamlined operations, and improved customer experience, while also promoting transparency and accessibility. It is justified as necessary to meet online-service expectations, modernise old systems, and sustain previous investments.

In a nutshell, they are relying on IT investment to improve how council work gets done so services are delivered more efficiently and conveniently. More importantly, they are relying on them to balance budgets through efficiency dividends from process automation and use of artificial intelligence.

How that bet goes wrong (in real life, not in the plan)

In these plans, some councils provide detailed action plans for IT investment. They describe how the investment in enterprise IT/digital/artificial intelligence (AI) will pay dividends through increased efficiency and better decision making. Few include quantifiable measures, like hours of customer/staff time saved, time or money saved from improved service performance, or number of blocked cyber threats.

Most make more general statements, such as IT investment improving ‘integration, efficiency, service responsiveness, analytics, and data protection’. They tend to flag things like AI and emerging tech as ‘disruptive’, and say they will need continued ‘exploration, upskilling and adoption’ to capture opportunities and maintain service effectiveness.

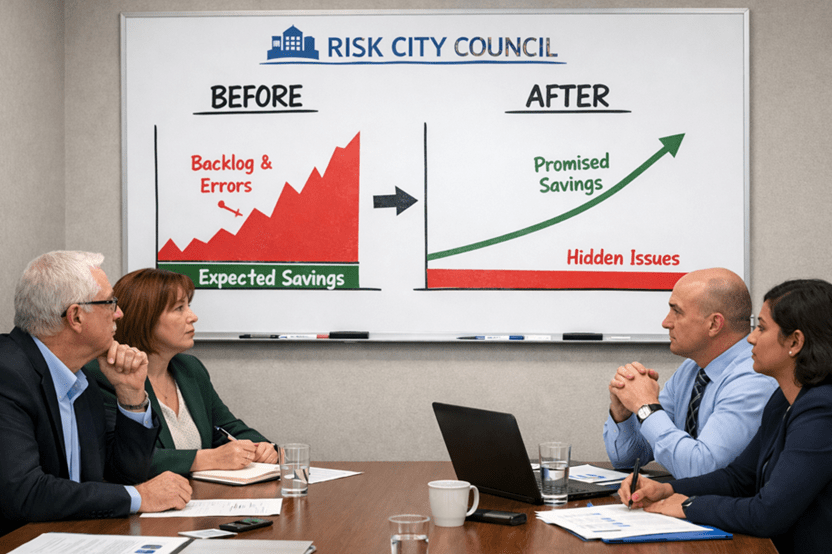

In all cases, there are lots of red flags. Savings are assumed to come from unspecified efficiencies, even when the way services are delivered hasn’t been optimised. Many benefits depend on behaviour change by people across the organisation, not just installing new software. None consider the cost shifting that happens when you reduce visible headcount but increase hidden work in data cleansing, workarounds, exception handling, and vendor dependency. Finally, they underestimate the cost of learning, backfilling, training, retrospective process redesign, change fatigue, and the productivity dip experienced after go-live.

A major IT investment isn’t simply a technology purchase. It’s a high-risk intervention in a complex socio-technical system. If you don’t understand the system first, IT will amplify the waste, workarounds, delays, and blame that is already there.

Here is how it can play out…

“At the planning counter, the new system looked slick—until the first week of lodgements. Applications bounced back for “missing information” that had already been provided, just in the wrong field. Staff spent mornings ringing applicants to re-collect the same details, then re-attaching the same documents. Phone calls doubled, mostly “Can you just tell me where it’s up to?” The dashboard said turnaround times were “on track” because the clock stopped during “awaiting customer” loops.

Meanwhile in local laws, officers found the system couldn’t handle the real-world exceptions. So, they started writing “manual notes” in notebooks and emailing themselves reminders. A shared spreadsheet reappeared to track cases the workflow couldn’t represent. At go-live, the backlog quietly grew: more clicks, more steps, more handoffs. Complaints rose—missed follow-ups, inconsistent decisions, people repeating their story. The weekly report stayed green, while the work moved off-system to get done.”

So, what can councils do?

The good news is that there are people trying to help councils to get major IT investments right.

Three due diligence tests before approving a major IT investment

Be pessimistic on purpose

This is the advice from Professor Robin Gauld and Professor Shaun Goldfinch in their book ‘Dangerous Enthusiasms: E-government, computer failure and information system development’. Across their work on public-sector IT investment failures, the recurring message is that large, ambitious, long-horizon projects routinely over-promise and under-deliver, especially when leaders get swept up in ‘e-government‘ enthusiasm and underestimate complexity and control problems.

It is noteworthy that the Victorian Auditor-General’s IT better-practice guidance explicitly points readers to ‘Dangerous Enthusiasms’ as a key reference.

Gauld and Goldfinch’s advice is blunt:

Assume forecasts are biased (i.e. the cost, time, and benefits) and treat the business case as a claim to be tested, not a plan to be accepted and implemented.

Keep aims modest and measurable, and avoid ‘everything at once’ transformations.

Prefer modular, incremental projects with real-world checkpoints and the ability to stop without catastrophe (no ‘big bang’ that can’t be unwound).

Governance must surface bad news early (i.e. not just traffic lights, milestones, and spend-to-date). When control is mostly through reports and committees, failure can occur quietly.

Knowledge first, IT last

Professor John Seddon has supported service improvement in public and private organisations for over three decades. He advises ‘fix the method (i.e. way of delivering a service) before digitising it’ (i.e. configuring or coding IT software to support delivering the service). His consistent warning is that public services go wrong when leaders manage by targets, budgets and functional silos instead of studying demand and improving end-to-end service delivery. In those circumstances, digitisation often codifies the wrong work (including avoidable and capacity-stealing failure demand) and makes it harder to change later.

Before making a major IT investment, Seddon says:

Study real demand (i.e what matters to residents, what triggers customer contacts, rework, complaints, and escalations/follow-ups).

Redesign the service against purpose (i.e. ‘outside-in from the viewpoint of the customer) and variety in demand first; only then decide what IT software supports delivery of the improved service.

Be suspicious of ‘standardisation’ being sold as creating efficiency when the actual demand is variable and contextual (i.e. planning, local laws, assets, customer requests, aged services interfaces).

Measure capability and flow, not just activity like the calls handled, jobs closed, or milestones met.

Design for work-as-done, not work-as-imagined

Sidney Dekker’s core field is human factors/safety science: how people and technology interact in real work, why ‘human error’ is usually a symptom of deeper system conditions, and how complex organisations drift into failure over time. A major IT investment is a socio-technical change: it rewires workflows, decision rights, handoffs, and defines what ‘good work’ looks like. Dekker has studied the exact failure modes that show up and he specialises in better governance processes.

If you apply Dekker’s thinking to a council IT investment, the practical takeaway is:

Start with ‘work-as-done’ before procurement. Shadow frontline staff, map handoffs, exceptions, and the ‘real’ rules people follow to keep services moving, especially services with high variety like planning, local laws, customer requests, and asset maintenance. Then design the system and its supporting IT around that reality.

Expect workarounds and treat them as intelligence (i.e. signals of a mismatch), not as misconduct. Workarounds usually signal the system doesn’t match the reality for workers.

Look for drift signals: rising exceptions, backlog, duplicate handling, staff ‘shadow’ systems, increased complaints – even when (perhaps, especially when) if the project dashboard is green.

Build a learning response: safe pilots, parallel runs, rollback plans, strong user support, and time for training/practice. Otherwise, time and budget pressure will force risky shortcuts.

Make governance ‘just’ and inquiry-based: when things go wrong, ask “how did this make sense at the time?” so you uncover the system conditions that create failure (rather than hunting a culprit).

What are useful questions to ask before approving a major IT investment?

Based on the advice of Gauld and Goldfinch, Seddon and Dekker, there are three sets of questions to ask:

Set 1 – Method (Seddon): Ask for evidence – the demand study, failure demand estimate, and before and after measures. Make sure you have answers to these questions – What service study have we done? What demand did we observe? What did we change in the service design before identifying the potential new IT software?

Set 2 – Ambition (Gauld/Goldfinch): Ask for evidence – staged scope, kill switch criteria, and the independent audit/review arrangements. Make sure you have answers to these questions – Exactly what have we done to reduce project complexity? Have we looked at modular scope, short horizons, staged implementation, and independent reality checks?

Set 3 – Drift (Dekker): Ask for evidence – what are the rollback and continuity plans, and how will we detect “drift” early? Make sure you have answers to these questions – Are we looking for, and planning to respond to, staff workarounds, increasing exceptions, backlog growth, manual rekeying, and community complaints?

How can you help yourself?

The sets of questions (really, just due diligence tests) are useful, and I have identified three authoritative sources. There are many more sources of advice. If you are curious and want to know more, try asking ChatGPT or Copilot (or your favourite Ai) this question:

“Find credible, citable evidence (auditor-general reports, VAGO/GAO/NAO/ANAO, peer-reviewed studies, and major post-mortems) of enterprise ERP/CRM/asset IT failures in the public sector. For each case, summarise: what was promised, what happened, root causes, early warning signs, quantified impacts (cost/time/service), and 10 governance actions a council can take to reduce risk. Include citations and links.”

If you really want to tighten up your search, add:

“Prioritise sources from audit offices and primary documents; avoid vendor marketing; include publication dates and direct quotes under 25 words.”

Some final words…

Councils are looking for ways to respond to the challenges of population growth, changing community expectations, and the rate cap. In their long-term plans they are relying on major IT investments to deliver reductions in expenditure through increased productivity, better decisions, and improved customer service. It is a big bet. Firstly, because major IT projects are difficult and exceed the capability of councils to implement. Secondly, they are difficult to govern and there is a real risk of over optimism and drift that gets the council into difficulty before it is recognised. Lastly, unless services have been reviewed and optimised, the implementation of an enterprise IT system will only cement in place inefficiencies and waste.

Before deciding, ask the right questions about what is proposed and why.

A cautious councillor can ask for the IT supplier to carry more risk for their technology. This happens with aquatic facility construction where councils now ask the architect and builder to carry risk for Greenstar compliance and they reduce contract payments if the target Greenstar rating is not achieved. You can also ask for evidence of the success of previous IT installations. This could be at your own council for any major IT change in the last 10 years – ask: What were the reasons for the investment and were the benefits realized? How do you know? The vendor should be able to provide detailed analysis of their success in previous installations, including lessons learned and post-implementation reviews giving quantified achievement of benefits.

Before deciding, gather evidence on your organisations capability and performance of the software.

It is noteworthy that councillors are only given choices about the IT investment needed to improve organisational efficiency, make savings, and improve services. CEOs have decided that the only solution to the councils challenges will come in a cellophane wrapped box from someone else. They are channeling the council down this path and have excluded the alternative that they organise for the people managing the organisation to examine the services they deliver and improve them by focusing on what customers need and expect. It is easier to place a bet on someone else’s solution to your problem than to develop your own.

Before deciding, know what you are betting on.

References

It’s the System, Stupid! Radically Rethinking Advice, AdviceUK, 2008.

Pessimism, Computer Failure, and Information Systems Development in the Public Sector, Shaun Goldfinch, 2007.

Drifting into failure: theorising the dynamics of disaster incubation, Sidney Dekker and Shawn Pruchnicki, 2013.

Note: the podcast was created using NotebookLM.

Additional reading: 294 – If the Vendor Won’t Bet on Savings, Why are you?