Posted by Lancing Farrell 1250 words

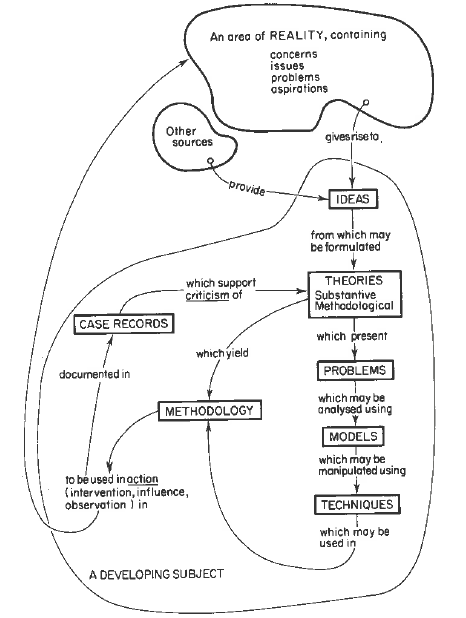

Systems Model, Peter Checkland, 1981.

Systems thinking has featured in a number of posts (see Some types of thinking observed in local government, Classic paper: ‘Forget your people – real leaders act on the system’. John Seddon, Applying the public value concept using systems thinking in local government). As someone with an interest in systems thinking I felt it deserved some discussion in the context of local government using ideas gathered from Peter Checkland, Alistair Mant and John Seddon.

The cover of Peter Checkland’s book ‘Systems Thinking, Systems Practice’ says that it is about the ‘interaction between theory and practice of problem solving methodology’, as derived from a decade of action research. It is a seminal text on the ‘meta-discipline’ of systems thinking.

Checkland has set out to ‘develop an explicit account of the systems outlook’ and, based on that view, to ‘develop ways of using systems ideas in practical problem situations’. The book is about the ‘use of a particular set of ideas, systems ideas, in trying to understand the world’s complexity’.

“The central concept ‘system’ embodies the idea of a set of elements connected together which form a whole, this showing properties which are properties of the whole, rather than properties of its component parts.”

Systems thinking is centred on the concept of ‘wholeness’. In some ways it is a reaction to the classical scientific method, which emphasises ‘reducing the situation observed in order to increase the chance that experimentally reproducible observations will be obtained’. Eliminating variables in order to study something to determine cause and effect is useful but ultimately limiting in complex systems where the interactions of all variables matters.

Systems thinkers have called it ‘organised complexity’ to describe the space between ‘organised simplicity’ and ‘chaotic complexity’. In some ways it is seeking to understand the simplicity that exists on the far side of complexity. In a nutshell, systems thinking is concerned with organisation and the principles underlying the existence of any whole entity.

Australian management author, Alistair Mant, describes two types of systems in his book ‘Intelligent Leadership’. He calls them the ‘frog’ and the ‘bicycle’ systems and he believes that leaders need to be able to distinguish between the two systems when applying systems thinking and directing a change and shift in systems. He sees ‘pointing systems in intelligent directions’ as one of the critical leadership responsibilities.

Frogs and bicycles are metaphors for different kinds of systems. The essential difference lies in the relationship of the parts to the whole. A bicycle can be completely disassembled and then reassembled with confidence that it will work as well as before. This is not possible with a frog. Once you remove a single part the whole system is affected instantaneously and unpredictably. Furthermore, as you continue to remove parts the frog will make a ‘series of subtle, but still unpredictable, adjustments in order to survive’.

“This sort of system, at a level beneath consciousness, wants to survive and will continue for an astonishing length of time to achieve a rough equilibrium as bits are excised – until it can do so no longer. At that point, again quite unpredictably, the whole system will tip over into collapse. The frog is dead and it won’t help to sew the parts back on.”

This is a salient warning for those planning to intervene in a system without due care. Mant believes that most big organisational systems contain bits of frog and bicycle systems. He says that the bicycle parts can be hived off and reattached in a new way without harming the overall system, but that the frog parts are really the core process. In a way, he is describing systems at two different levels – the component-level (bicycle) and the system-level (frog).

Checkland says that ‘any system which serves another cannot be modelled until a definition and model of the system served is available’. This approach should prevent action on component ‘bicycle’ systems occurring before the potential implications for the whole ‘frog’ system is understood.

In common with Checkland, Mant holds the view that systems are complex and need to be considered as a whole. The systems model developed by Checkland (shown above) illustrates the process of systems thinking. He says that it starts with a ‘focus of interest’ or set of concerns that exist in the real world. This could be a problem or something about which we have aspirations. This leads to an idea. From that idea two kinds of theory can be formulated:

- Substantive – theories about the subject matter.

- Methodological – theories about how to go about investigating the subject matter.

Once theories exist, it is possible to state problems not only as they exist in the real world, but also as ‘problems within a discipline’. For example, engineering, chemistry or town planning. All of the resources of the discipline (i.e. previous problems, its paradigms, models and techniques) can then be used in an appropriate methodology to test the theory.

The results of this test, which involves action in the real world (i.e. interventions, influencing and observation), then provides case records of ‘happenings under certain conditions’. These are the crucial source of criticisms that enable better theories, models, techniques and methodologies to be developed. It is the improvement loop.

For those proponents of the Vanguard Method this might be starting to sound familiar. John Seddon has developed an application of systems thinking in organisations that has demonstrated its value in improving organisational systems. The Vanguard Method has the following steps:

- Check

- What is the purpose of this system?

- What are the types and frequencies of customer demand?

- How well does the system respond to demand?

- What is the ‘flow’ of work?

- What are the conditions that make the system behave this way?

- Plan

- What needs changing to improve performance?

- What action could be taken and what would we predict the consequences to be?

- Against what measures should action be taken?

- Do

- Take the planned action and monitor the consequence in relation to the purpose.

It features systems thinking in the need to understand a concern in the real world (what are the demands?), develop a theory or approach to improvement (what needs to change?), and then seeks to implement that action and monitor consequences (how can the approach be improved?).

“The outcome of studying the work in this way is a system picture that puts together everything that has been learned and which illustrates the dynamics of the particular service.” John Seddon.

Mant says that most complex systems containing and serving people have ‘natural properties’. Effective management aligns itself with the natural flows and processes to help them along – like a leaf floating on water running in a stream that naturally takes it to its destination. Bad or dogmatic management fails to recognise these natural properties and attempts to ‘shoehorn the system into shape’ to meet externally determined priorities. This has been identified as a problem for public sector management in a previous long read post.

Local government has spent too long looking out of the window hoping to see a ’business-like’ way of managing that will solve all of its problems, rather than having the confidence to work out what is needed from first principles. It is vulnerable to the next externally imposed management fad.

Seddon is particularly harsh in his judgement of public service reform for the past 35 years in Britain. He describes the contribution of each Prime Minister in some detail. Overall, he paints a picture of political interference and the projection of a narrative that has primarily focussed on reducing costs, yet costs have increased. This is principally because they have failed to understand the system. The complexity of systems containing and serving people has been overlooked.

Checkland, Peter, 1981. ‘Systems Thinking, Systems Practice’.

Mant, Alistair, 1997. ‘Intelligent Leadership’.

Seddon, John, 2014. ‘The Whitehall Effect’.