1700 words (18 minutes reading time) by Carole Parkinson

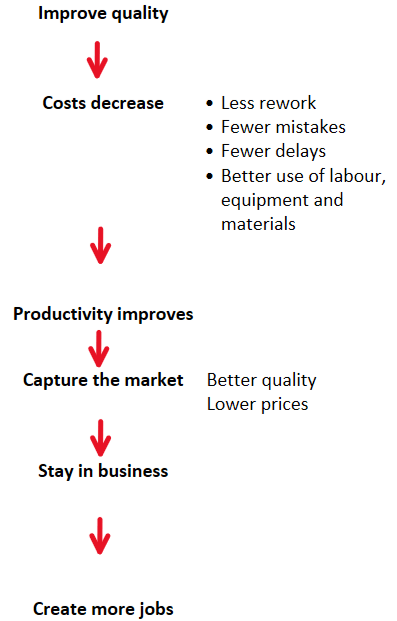

The Deming chain reaction

Tim Whistler cuts straight to the chase. In the case of his latest piece, I think he could do with a little nuancing of what he is proposing. His description of the disruption to ensue if councils can’t manage their finances with a rate cap is probably accurate, but also, avoidable.

I have been talking to executives at councils and it is true that they are grappling with defining and agreeing on what they need to do. Everyone involved in leadership seems to be pulling in a different direction – Finance wants direct funding cuts to balance budgets now; Directors want efficiency drives to fit services into budgets as soon as possible; Councillors want to cut services they think the State should provide and avoid electoral backlash when they stand for re-election in 2028. It is a vicious cycle.

I have a more immediate approach, which neatly fits with Whistler’s focus on infrastructure as the big service, allocating capital first, and, most importantly, reducing expenditure where you should, not just where you think you can.

I am going to look at reducing expenditure because it seems to be the common goal of everyone involved.

“Councils need to work out how to meet the needs and expectations of the community at lower cost.”

This sounds simple and there are many examples of organisations finding ways to do it. One that I am familiar with is the work of W. Edwards Deming, in particular his ‘chain reaction’ that I have shown above. Deming’s way of thinking contributed to Japanese dominance in car manufacturing and development of the most successful manufacturing system in the world. On the way they significantly reduced costs.

W. Edwards Deming

There are lots of ways that Deming’s thinking has been put into practice. Some of the better known examples are Total Quality Management, Quality Circles and Lean. No one in manufacturing doubts the value in these methods to improve quality. They have proven their value over time.

It is different in service delivery. The intangibility of outputs of services makes them more difficult to understand. This makes performance harder to measure. In the absence of effective performance measurement, the benefits from improvement efforts are hard to evaluate. In that situation, every idea about how to improve is seen to be as good as any other idea.

I have found that service improvement in local government is often driven by leader opinions and preferences, which prevail in the absence of cold hard facts from proper measurement of performance. There have been previous posts about the management fads that councils have adopted in the name of continuous improvement, none of which has been sustained.

The fact that every new leader feels the need to bring in their own method for change suggests that no other method has been effective. Or, perhaps, no one has bothered to measure the effectiveness properly. Whichever it is, it doesn’t matter, Think about the last time a new CEO started in your organisation – did they spend time understanding what was already happening to optimise it, or did they just bring in new people and a new method?

I suppose, I am advocating yet another method by adapting Deming’s chain reaction for public services. The difference is that this method is based on decades of proven success. It is also a method suited to the challenges of today because it starts with quality of service as determined by the customer (who could be a citizen, consumer, user, resident, ratepayer, etc. – whatever term you want to use for the person receiving a council service).

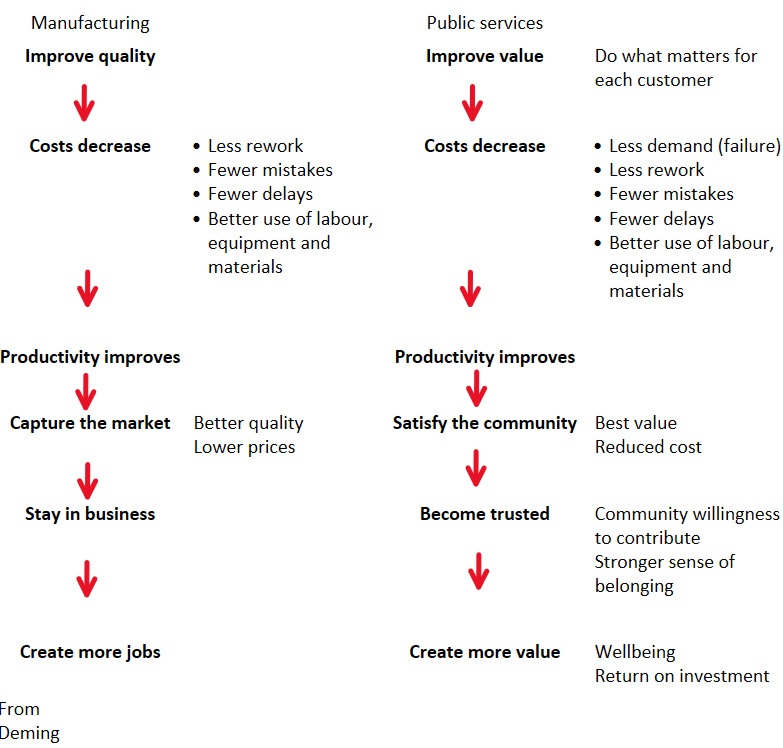

Public service chain reaction

I have taken the liberty to translate Deming’s chain reaction from a manufacturing context into a public service context. I have done this by drawing on the work of John Seddon in his Vanguard Method. I will explain what I have done.

Improve quality/improve value

Deming starts with an unrelenting focus on improving quality. The required quality standard must be clear and repeatable. Manufacturing systems are suited to this approach if management set the aim of the system and the standard to be achieved. In contrast, services require the standard set by each customer to be met each time they place a demand on the system.

“Customers must get what they want, when they want it, and how they want it.”

Henry Neave

I have described this as ‘doing what matters for each customer’. I am sure John Seddon would describe it as understanding the customer problem to be solved, what matters to them about how they get help to solve it, and what would be perfect if you could do it. Only when you are perfect will the value required by the customer be provided at lowest cost.

When you are talking to managers, the issue of costs always comes up at this point. Without exception, I have found that when I say that giving each person exactly what they want will be the lowest cost service, they disagree. Typically, they argue that costs will increase because the way to decrease costs is through standardisation and economies of scale. It is what they spend most of their time trying to do without realising it doesn’t work.

Costs decrease/Costs decrease

As Deming points out in his chain reaction, when quality is right, costs decrease because there is less rework, fewer delays or errors, and better utilisation of people, equipment and materials. The additional benefit in public services is that demand decreases. The type of demand that decreases is failure demand, which is created when something about the quality of service isn’t right the first time. Seddon describes this as fulfilling customer purpose.

Seddon coined the term failure demand and his work has shown how it can take up 30 to 80% of your productive capacity. Let’s say it is 50%. Imagine that, half of your resources are being used to do something that shouldn’t need to be done. What if they were available to direct towards activities actually creating value for customers? How would that start to help you to meet the needs and expectations of customers at lower cost?

“It (failure demand) is demand caused by a failure to do something or do something right for the customer. Customers come back, making further demands, unnecessarily consuming the organisation’s resources because the service they receive is ineffective.”

John Seddon

Productivity improves/Productivity improves

When there is less failure demand, less rework, fewer delays and errors, and better utilisation of resources, you get increased capacity and improved productivity at no extra cost. And, customers are satisfied. In public services, this plays out in some important ways. The first is that people know they are getting best value. In Victoria, this is a legislated objective of every council when spending ratepayers money. Secondly, when people get great value and costs don’t go up, they are much more likely to support what the council is doing. They may even support an application for a higher rate cap!

Capture the market/Satisfy the community

This sort of community satisfaction leads to trust. The issue of trustworthiness is central to most people’s relationship with government across the world. When people feel they cannot trust the government they support resist tax increases and support destructive change. In many ways, the rate cap in NSW and Victoria represents a taxpayer revolt. The State government correctly identified that it would be electorally popular for them to stop councils raising the rates. Until councils build trust in their community, the rate cap will be here to stay and higher caps will be difficult to achieve before there is a financial crises.

Stay in business/Become trusted

It can get better than that though. When people feel that they are getting great value from their council and they trust them, they are more likely to contribute to creating value. They might mow their neighbour’s long grass on the nature strip instead of complaining about it to the council. They might pick up litter in their street instead of asking the council to do it. They might put the correct wastes in each bin. This all helps to reduce costs.

When people engage with their neighbours and start to care about the place they live in, their sense of belonging increases. They create social capital in new relationships with neighbours when they help each other instead of ringing the council about problems. People will talk to each other about issues. Imagine, less phone calls dobbing in a neighbour because of a barking dog or loud music. Less demand for community transport because people drive their neighbour to their doctors appointment. Less demand for waste bins to be rolled out and in by the collection truck driver because neighbours help each other. Again, costs go down.

Create more jobs/Create more value

More jobs is a broad societal benefit created by successful companies. I think the equivalent for a council is to help create even more value for its community. A council that successfully meets the needs and expectations of its community through the services it provides today is stopping things getting worse in the lives of residents, rather than making life better for them.

Think dog control, parking enforcement, or youth services – all services that react to problems to contain them. Getting better at these services doesn’t make life better for everyone. Working with communities to make life better requires effort to understand what people need to live good lives, not just what they don’t want to have happen to them. With understanding, councils can start to improve how cities are designed so they work for people instead of improving the services that mop up the messes.

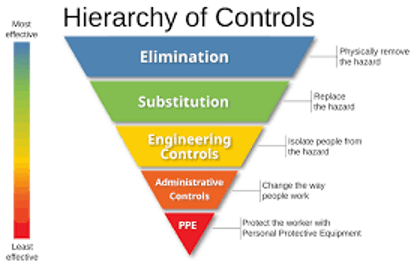

Even if the council was 100% efficient spending ratepayers money on reactive, ‘mop up’ services, it would create less value that designing out the problem. It is like the hierarchy of controls in occupational health and safety (OHS), which we all understand, accept and use. Elimination is better than more controls, however diligently those controls are applied.

The hierarchy of occupational health and safety controls

It can be difficult to measure the success of efforts to improve community wellbeing to determine whether there is a return on the investment. One way, albeit a lagging measure, is to record incidents of distress in the community and determine whether there are more (poor performance) or less incidents (better performance) occurring. Councils have the same challenge in measuring OHS performance but they accept measures that show an increase or reduction in the number or severity of workplace incidents as a measure of success.

Conclusion

Councils are making decisions in the executive suite or council chamber to cut expenditure and services without understanding the impact on the community and its wellbeing. Worse still, the typical approach to cost cutting is to shave little bits off lots of budgets and leave it up to relatively junior officers to determine how they will respond to the cut. It is an uncontrolled change process that gives potentially hundreds of officers the responsibility for changing services to deliver them with reduced funding. Talk about choosing your own adventure! I wonder what the Audit and Risk Committee thinks about that risk.

Deming has proven over time to have implementable and effective ways of thinking about organisational improvement. It’s time to dig out his books and start applying his thinking to council services. Or just hire one of the many companies already helping councils with this approach to service improvement.