870 words (10 minutes reading time) by Colin Weatherby

I was talking to a former colleague recently and she described the decision making by her new CEO as ‘OECD’. I asked her what she meant. She said that when faced with any decision, the CEO would look for solutions that are:

O = obvious (i.e. he won’t have to explain the decision because it will be obvious to everyone).

E = easy (i.e. easy to act on the decision and within his capability to implement it).

C = cheap (i.e. it won’t cost any more money to act on the decision or it will immediately cost less).

D = done (i.e. when action has been taken, the result will be obvious to everyone).

I asked her how this was working out for her.

She said it limited discussion within the organisation and senior officers were learning that asking for decisions when the solution is OECD is successful. Solutions that are the opposite (i.e. difficult to explain and difficult to implement, potentially more expensive (even if it is in the short-term) and hard to see when action has been completed) are less likely to be supported.

I found this slightly depressing. If a CEO starts to only support solutions that are OECD it is likely to result in more long-term problems and costs and is unlikely to see any ‘wicked’ problems being effectively addressed. In fact, worse, it encourages senior leaders not to see those problems. She said that across the organisation leaders are busy only finding problems with OECD solutions or describing all solutions to appear to be OECD. The organisation is becoming reductionist at a time when, across the sector, people are starting to apply systems thinking to council services.

It reminded me of George Lakoff saying that language is at the heart of many problems. Perhaps the CEO is not able to express their desire for action in any other way? In particular, Lakoff laments the absence of words to describe systemic causation when we have many words to describe direct causation. It plays into the hands of leaders who want everything to be simple.

I asked ChatGPT to help me out with what Lakoff means:

Direct Causation

Direct causation, as described by George Lakoff, refers to a straightforward, linear understanding of cause and effect. In this view, an action or event A directly leads to an outcome or event B. It’s a simple, one-to-one relationship where A causes B, and this causal link is often perceived as deterministic. In essence, direct causation implies that if you change A, you can predictably and directly change B.

This concept aligns with our everyday, intuitive understanding of causation. When we turn the key in our car’s ignition, it directly causes the engine to start. When we press a light switch, it directly causes the room to be illuminated. Direct causation provides a sense of control and predictability, making it a foundational aspect of how we navigate the world.

Systemic Causation

In contrast, systemic causation, as proposed by Lakoff, represents a more intricate and interconnected view of causality. It acknowledges that many real-world phenomena involve a web of causes and effects, often operating within complex systems. Rather than a linear, direct link, systemic causation recognizes that multiple factors and interactions contribute to an outcome.

Systemic causation embraces the idea that our world is full of feedback loops, interdependencies, and dynamic relationships. Changes in one part of a system can lead to ripple effects throughout the entire system, influencing various components and outcomes. This perspective challenges the notion of strict determinism and highlights the importance of context, feedback, and unintended consequences.

Systemic causation, because it is less obvious, is more important to understand. A systemic cause may be one of a number of multiple causes. It may require some special conditions. It may be indirect, working through a network of more direct causes. It may be probabilistic, occurring with a significantly high probability. It may require a feedback mechanism. In general, causation in ecosystems, biological systems, economic systems, and social systems tends not to be direct, but is no less causal. And because it is not direct causation, it requires all the greater attention if it is to be understood and its negative effects controlled.

George Lakoff

What are the implications?

Understanding systemic causation is vital for leaders in the public sector. We hear a lot about ‘wicked’ problems, which usually means they are complex issues with multifaceted systems and numerous interconnected variables. Approaching these problems with a direct causation mindset can lead to oversimplified solutions. Instead, decision makers must consider the systemic nature of these challenges, addressing root causes and anticipate unintended consequences.

While direct causation serves us all well for simple, everyday situations, addressing systemic causation is essential when dealing with complex, interconnected systems and societal challenges. Embracing systemic causation invites us to appreciate the intricacies of society and the profound implications of actions that resonate far beyond their immediate, direct effects. It encourages us to think in terms of feedback loops, interdependencies, and holistic solutions, ultimately leading to better informed decision-making and more effective problem-solving in an increasingly complex world.

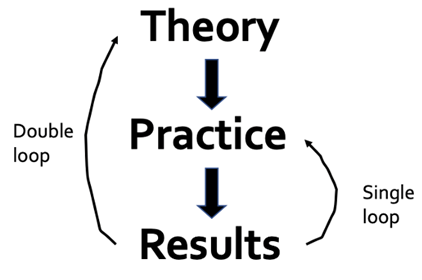

OECD thinking is single loop and isn’t going to effectively address challenges like the rate cap or the housing shortage or climate change. It risks locking the organisation into making minor adjustments to address issues. This tends to maintain the status quo rather than encouraging innovative thinking. It avoids questioning fundamental assumptions. It addresses symptoms as they arise, rather than anticipating and preventing them from occurring in the first place. Focusing on incremental adjustments doesn’t lead to the most efficient or effective solutions when a more transformative change is needed.

This is why many organisations complement single-loop thinking with double-loop thinking to critically examine underlying assumptions and the possibility of restructuring systems and processes. Double-loop thinking encourages a deeper level of learning, making it better suited for local government today.

An unfortunate characteristic of some councils in Victoria seems to be that leaders label anyone interested in systemic causation as ‘theoretical’ and, therefore, impractical and not useful.

It locks in single loops.

‘Global Warming Systemically Caused Hurricane Sandy‘ by George Lakoff, Reader Supported News, 30 October 2012

Footnote

I received a DM on this post raising a related issue. The short-term nature of CEO contracts, and the link between CEO contract renewal and elections (i.e. where their 5 year contracts meet the 4 year election cycle), creates a very small ‘sweet spot’ for CEOs or Councils to act. And they need to be in sync for any big or transformative decisions to be made.

Perhaps, OECD is a natural reaction to the these features of local government since the reforms of the 1990s.

Pingback: 250 – A Call to Transform Local Governance: Beyond Disappointment, Toward a Resilient Future | Local Government Utopia